Photoinitiators are small molecules that are sensitive to light. Upon light absorption, they undergo photochemical cleavage to produce reactive species (either free radicals or a Bronsted or Lewis acid) that will interact with the active components in the liquid formulations. In other words, photoinitiators take the energy from light, transform it into chemical energy that will in turn, induce a chemical reaction known as photopolymerization (or radiation curing). The end product of this reaction is a highly cross-linked (photo)polymer.

There are 2 classes of photoinitiators: Type I and Type II

Type I photoinitiators are those that undergo unimolecular bond cleavage after absorption of light to render the reactive species. No other species are necessary in order for these photoinitiators to work.

Type I photoinitiators are those that undergo unimolecular bond cleavage after absorption of light to render the reactive species. No other species are necessary in order for these photoinitiators to work.

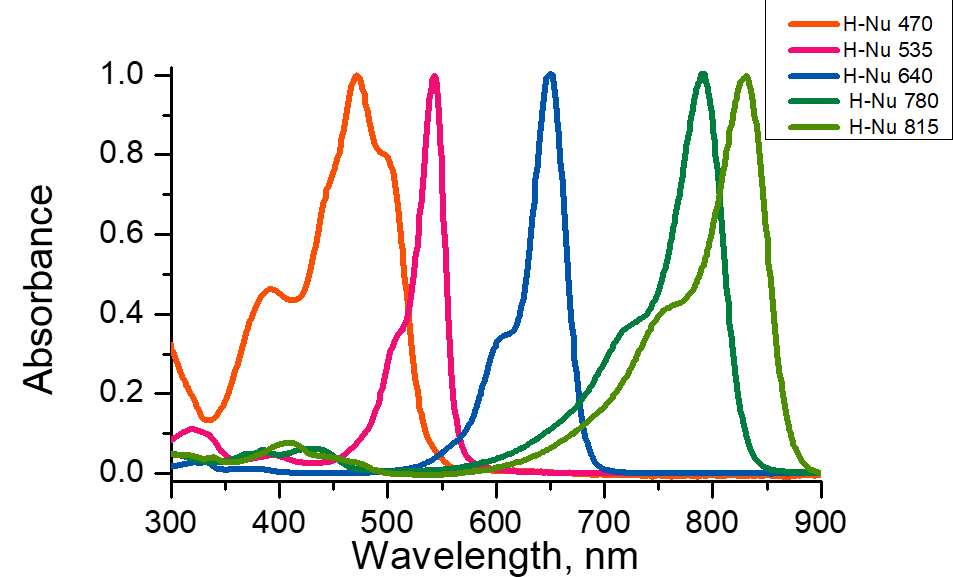

For the photopolymerization process to be successful, it is necessary to have an almost perfect overlap between the absorption bands of the photoinitiator and the emission spectrum of the light source that will be used for curing. A poor match will result in a poor cure or no cure at all. Furthermore, in order to ensure the curing process will be as successful as possible, there should be minimum competition for light absorption (or scattering) from other species in the formulation.

As mentioned above, the photopolymerization process can undergo two different mechanisms: Free radical or cationic. Due to the different nature of the reactive species formed in each process, it is also key to choose the photoinitiator capable of inducing the right kind of photopolymerization.

Free radical photoinitiators are used in the photopolymerization of acrylate or styrene based resins. This is probably the most common type of photopolymerization used. The radiation curing can be performed using UV or Visible light, and in some instances, near IR photoinitiators have been developed (check our H-Nu Blue and H-NU near IR series). The photopolymerization process immediately stops once the irradiation ceases. For this reason, it is extremely important to know the exposure time required to obtain a fully cured photopolymer. Free radical photopolymerization tends to be a “faster cure” compared to cationic photopolymerization.

A main drawback of free radical photopolymerization is the susceptibility to oxygen inhibition, which can lead to “tacky surfaces”.

Cationic photoinitiators are used to initiate the photopolymerization of epoxy resins. Just as the free radical process, the curing process can be carried out with UV or visible light. Unlike free radical, the photopolymerization process in cationic systems continues even when the irradiation of light has stopped. Cationic systems are free of oxygen inhibition (unlike free radical systems), but a drawback could be the longer times required for the cure to take place.

In conclusion, selecting a photoinitiator that is appropriate for the resin substrate and lamp/light source used is key to obtaining the perfect cured photopolymer.